What is a direct statutory demerger and how can you use it?

Statutory demergers are often described as the ‘go-to’ method of demerging, as they are quite literally written in the legislation. Due to their simplicity, i.e. not incorporating or liquidating companies, they are typically cheaper to implement and more straightforward.

For those that meet all the relevant conditions, they are extremely effective. However, in practice, they are infrequently used due to the numerous conditions attached. Attempting a statutory demerger without meeting these requirements can lead to tax inefficiencies, highlighting the importance of seeking professional advice prior to demerging your business.

There are two types of statutory demergers: direct and indirect. This blog focuses on direct statutory demergers.

Example

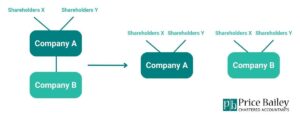

A straightforward example of a non-partition direct statutory demerger involves Company A, which operates a trade (Trade A), and is owned by Shareholders X and Y. Company A owns Company B, which also operates a trade (Trade B). In this case, Company B is demerged from Company A so that it is owned by Shareholders X and Y directly. It is important to note that Shareholders X and Y hold the same proportion of shares in Company B as they own in Company A.

What criteria needs to be met for a statutory demerger?

A direct statutory demerger is one of the simplest types of demerger, as it doesn’t require incorporating a new company.

Using the example above, Company A is effectively distributing its shares in Company B to the shareholders. This distribution is exempt from Income Tax, provided specific criteria are met. These requirements include, but are not limited to:

- Company A must be a holding company of a trading group or a trading company , and remain so after the demerger. Company B must be a trading company or a member of a trading group at the time of the distribution.

- The demerger must involve the transfer of shares in a 75%+ subsidiary to the shareholders.

- The demerger must be for the benefit of the trade(s)

- The demerger must not be in anticipation of cessation or sale of one of the trades.

Other strict requirements also apply in order to be exempt from Income Tax and Corporation Tax.

It is possible to obtain advance clearance from HMRC that they are satisfied that the distribution will be exempt, and we would strongly recommend that such clearance is sought prior to implementing any demerger transaction.

What happens if the conditions aren’t met?

Failure to meet the required conditions does not necessarily prevent the demerger from taking place, provided there are sufficient distributable reserves. However, there would be tax implications of the demerger, and an Income Tax charge for the shareholders would arise on the shares distributed.

Are there any other charges to be aware of?

The main taxes to consider following a direct statutory demerger are:

- Income Tax (the shareholders have received a distribution)

- Corporation Tax (Company A has disposed of shares)

- Chargeable Payments (see below)

As with the other types of demergers e.g. s110 or a reduction of capital, additional taxes such as Capital Gains Tax, Stamp Duty Land Tax (SDLT), Inheritance Tax and VAT may also need to be considered.

What about the Substantial Shareholdings Exemption?

Using the example at the beginning of the blog, when Company A disposes of its shares in Company B, the Substantial Shareholdings Exemption (SSE) may eliminate any tax charge.

If the SSE doesn’t apply, a Corporation Tax charge will arise for Company A based on the difference between the current value of Company B and its base cost.

This could be a definitive reason to consider alternative demerger options, such as an indirect statutory demerger, s110 or capital reduction demerger.

What about degrouping charges?

When a company leaves a group, if it has received any assets within the last six years from a group company a degrouping charge could arise. For example, if the original company (Company A) transferred property to the soon-to-be demerged company (Company B) in the six years prior to separating, and the demerged company still holds the property upon leaving the group, a degrouping charge may arise.

It is possible that any degrouping charge may be exempt if the SSE applies, but careful consideration will be required to ensure the demerger doesn’t trigger any unforeseen tax implications.

Similarly, SDLT group relief could be withdrawn if there was a transfer of land or property from Company A to Company B within the last 3 years.

What about chargeable payments?

The easiest way to describe what a chargeable payment is (and why they exist), is to use an example.

In our example at the start, Company B was demerged from Company A.

Following the demerger, Company B buys back some of its shares from the shareholders, or is liquidated. The shareholders would typically receive cash from the share buyback or disposal of their shares on liquidation, which could, without other rules, be subject to capital gains tax rather than income tax.

A chargeable payment would arise if this happened within 5 years of the demerger, and would result in the sum received being treated as income, and therefore subject to the higher income tax rates.

Effectively, the chargeable payment is aimed at preventing shareholders using a demerger to extract cash from the company in the form of capital rather than income.

If the payment received by the shareholders meets certain conditions and is for ‘genuine commercial reasons’, clearance can be sought from HMRC to confirm that it will not be treated as a chargeable payment.

Even if you meet all the conditions for a statutory demerger, is it recommended?

Whether a direct statutory demerger is the right choice depends entirely on the circumstances of the businesses involved. This is the simplest type of demerger to implement because it doesn’t require the incorporation of additional companies, making it cheaper from an implementation perspective.

However, there are extra administrative requirements to a statutory demerger that shareholders need to be aware of.

Once HMRC clearance has been obtained acknowledging that the demerger is going to be an exempt distribution, and the process is complete, a return must be submitted to HMRC within 30 days, giving full details of the transaction actually undertaken.

The directors and shareholders need to watch out for chargeable payments within the next 5 years and submit a return to HMRC within 30 days of any chargeable payment made.

As a direct statutory demerger is treated as a distribution, the company must have sufficient distributable reserves to lawfully make a dividend of the required size. Directors will need to confirm that these reserves are up to date, and declare their ability to make a lawful dividend.

Closing thoughts

While there are many conditions to meet for a direct statutory demerger to be efficient, it remains one of the simplest and most cost-effective methods, when weighing up all relevant factors. If chargeable payments are not expected in the next five years and the additional administrative requirements are understood and managed, this type of demerger could be a suitable option. We always recommend seeking professional advice when considering demerging your business, to ensure all relevant conditions, consequences and possible alternatives are considered.

We always recommend that you seek advice from a suitably qualified adviser before taking any action. The information in this article only serves as a guide and no responsibility for loss occasioned by any person acting or refraining from action as a result of this material can be accepted by the authors or the firm.

Have a question about demergers? Ask our team below...

We can help

Contact us today to find out more about how we can help you